Sunday, April 23, 2006

Friday, April 21, 2006

Introducing My Blog

Enjoy my Afghanistan blog and let me know what you think when you look at the photos and read my stories.

Cheers

Cheers

Kandahar Airfield

For ten months Kandahar Airfield (KAF) was home. The airfield, about five miles from Kandahar City, is a city unto itself, teeming with energy, filled with troops, dust, vehicles, machinery and civilian contractors. After I arrived at KAF in May 2004 the transformation I saw on Kandahar Airfield in those few months was tangible.

Along the perimeter road to the south, between a militia compound and a series of old bombed-out Soviet barracks, sits a fresh chain-linked fence topped neatly with a coil of razor wire. The fence wasn't there when I arrived. It pushes KAF farther south and one day will form the new perimeter after the Coalition returns the international airport terminal to the Afghans.

Behind the fence, a daily surge of construction vehicles, dump trucks, front loaders and flat beds hauling pipe and lumber work a seemingly endless task. Once nothing more than dirt and land mines, the perimeter road is now lined with gravel and chain-link, concrete-based fence posts and neatly printed warning signs every 50 meters.

After I'd been away from KAF for a week in those initial months, I realized the significant change in the camp as I drove down Screaming Eagle Boulevard past the air terminal. The once-dilapidated mosque adjacent to the terminal breathed anew.

When I arrived here, the Muslim holy place had the signature of mortar and rocket grenade blasts splashed on the outer walls. Chipped plaster inside and the crumbling walls outside have been repaired by Afghan workers. The spires, once crushed and rough, now shine smooth and bright blue against the mended white walls.

The troops, always active and bustling about camp, gave the airfield a vibrant edge. With missions as varied as their uniforms and appearances, service men and women plunged daily into the minutia of war fighting and rebuilding Afghan infrastructure. Logistics makes the combat effort possible, so, of the 5,000-plus troops on Kandahar Airfield, more than half provide support to the combatants.

As for Kandahar Airfield, it is here to stay. The funds to build the airfield and to push this piece in the global war on terror forward are sizable. The business of building bases isn't cheap, especially in southern Afghanistan. One estimate claims a billion dollars will be spent during the next five years on Kandahar Airfield and infrastructure in southern Afghanistan. The country only has 25 kilometers of railroad, so the ability to move trade goods and raw materials for construction is limited to trucks.

I would leave the airfield on operations sometimes for a week, sometimes just a couple days, escorting foreign correspondents around the southern provinces as they covered US forces.

Each time journalists arrived on the airfield wanting to cover the coalition’s efforts I gave them a tour in my issued Toyota pickup truck. I would drive them around the main loop through camp, past the stench of the burn pit and sewage pond. I’d point out the new modular metal units under construction which now house all the troops. I would show the amenities, the Post Exchange, the showers, the Internet cafe and I’d describe the various military units as we would pass each one.

My job in Afghanistan was to “facilitate media” and in that I helped them tell the stories of US forces operating from Kandahar Airfield.

Along the perimeter road to the south, between a militia compound and a series of old bombed-out Soviet barracks, sits a fresh chain-linked fence topped neatly with a coil of razor wire. The fence wasn't there when I arrived. It pushes KAF farther south and one day will form the new perimeter after the Coalition returns the international airport terminal to the Afghans.

Behind the fence, a daily surge of construction vehicles, dump trucks, front loaders and flat beds hauling pipe and lumber work a seemingly endless task. Once nothing more than dirt and land mines, the perimeter road is now lined with gravel and chain-link, concrete-based fence posts and neatly printed warning signs every 50 meters.

After I'd been away from KAF for a week in those initial months, I realized the significant change in the camp as I drove down Screaming Eagle Boulevard past the air terminal. The once-dilapidated mosque adjacent to the terminal breathed anew.

When I arrived here, the Muslim holy place had the signature of mortar and rocket grenade blasts splashed on the outer walls. Chipped plaster inside and the crumbling walls outside have been repaired by Afghan workers. The spires, once crushed and rough, now shine smooth and bright blue against the mended white walls.

The troops, always active and bustling about camp, gave the airfield a vibrant edge. With missions as varied as their uniforms and appearances, service men and women plunged daily into the minutia of war fighting and rebuilding Afghan infrastructure. Logistics makes the combat effort possible, so, of the 5,000-plus troops on Kandahar Airfield, more than half provide support to the combatants.

As for Kandahar Airfield, it is here to stay. The funds to build the airfield and to push this piece in the global war on terror forward are sizable. The business of building bases isn't cheap, especially in southern Afghanistan. One estimate claims a billion dollars will be spent during the next five years on Kandahar Airfield and infrastructure in southern Afghanistan. The country only has 25 kilometers of railroad, so the ability to move trade goods and raw materials for construction is limited to trucks.

I would leave the airfield on operations sometimes for a week, sometimes just a couple days, escorting foreign correspondents around the southern provinces as they covered US forces.

Each time journalists arrived on the airfield wanting to cover the coalition’s efforts I gave them a tour in my issued Toyota pickup truck. I would drive them around the main loop through camp, past the stench of the burn pit and sewage pond. I’d point out the new modular metal units under construction which now house all the troops. I would show the amenities, the Post Exchange, the showers, the Internet cafe and I’d describe the various military units as we would pass each one.

My job in Afghanistan was to “facilitate media” and in that I helped them tell the stories of US forces operating from Kandahar Airfield.

leishmaniasis

Near our patrol base in Zabol Province a father approached us asking for medical attention for his young son. He was suffering from leishmaniasis. The disease is caused when sandfleas burro into the skin to feed and live.

If he survives, he will be extremely scarred.

A description of the disease:

A group of diseases caused by parasitic protozoans of the genus Leishmania. It is transmitted by sandflies and are, in general, infections of the skin, mucous membranes, and certain internal organs by the parasites. Three major types of leishmaniasis occur in humans - cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral: In cutaneous leishmaniasis, also known as aleppo boil, aleppo button, Bagdad boil, Baure ulcer, Delhi boil, oriental sore, and tropical sore, the parasite causes lesions on the face, arms, and legs which begin as inflamed bumps and can turn into skin ulcers that take up to two years to heal. In mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, also known as American leishmaniasis, Chiclero ulcer, espundia, forest yaws, and uta, the parasite invades the mucous membranes and causes ulcers in the nose, mouth, and parts of the sinuses. This can result in lesions and deformity of the face. In visceral leishmaniasis, also known as kala azar (a Hindi term meaning "black fever") or dumdum fever, the parasite invades the spleen, liver, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and skin. Symptoms include fever, fatigue, enlargement of the lymph nodes, the spleen, and the liver, dizziness, weight loss, and secondary infections such as pneumonia, and it can be fatal if left untreated.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Monday, April 17, 2006

First Combat Op

Based in Kandahar in May 2004, I prepared for Operation Blue Candle, an Air Assault into Zabol Province. I needed to coordinate with the unit with which I was to travel for the mission. I wanted to move with the tip of the spear, what the Army calls ‘the main effort.’ In this instance it was Alpha Company 2-35 Infantry – part of the 25th Infantry Division.

Bravo Company was to move into position two days prior by ground transport to provide support forming the objective’s outer cordon. Alpha Company was then to fly in on Blackhawk helicopters and assault the first objective from the outset. I wanted to fly with Alpha and the Battalion Commander had given me latitude to do so, yet I had to clear it with the Company leadership.

The following dialogue is what I poured onto the page right after I initiated contact with the Alpha Company leadership. It is rough, has rough language and, I think, gives a taste of the military environment.

This was to be the first time since Vietnam that Alpha 2-35 Infantry would engage an enemy in combat. The pressure was on the leaders. I had been in Afghanistan only a few weeks. This was to be my first air assault in combat as well.

I've altered names to protect identities.

Alpha Company Commander - May 22, 2004

Captain Eric Arnold seemed well educated. He’d been to college, probably an ROTC grad at 22. Yet, for years he’s been around infantrymen, his language natural, base, straightforward and genuine, an infantryman’s language. No holds barred. I stood erect in the entry way to his quarters and listened as he laid it on the line.

“To be honest with you, I don’t fuckin’ want you on this mission.” He kept talking to me while searching for something, rifling through stuff on a shelf, then on his bunk, then lifting papers at his desk.

“I’ve got too many strap-hangers as it is,” he said.

An Airborne term - ‘strap hangers’ – these were jumpers who weren’t part of the unit who show up at the last minute and want to be manifested for a jump. What could be a good jump with people you trust turns into an unpredictable gaggle of people you don’t know.

“It’s nothin’ ‘gainst you personally, you may be a great guy, but I don’t know you, my guys don’t know you. YOU are a liability to my unit,” continuing to search for something.

“Fuckin’ strap hangers… I’ve got interrogators, FBI, THT, female search teams, chaplains AND their assistants … fuckin’ chaplains! I gotta a whole gaggle of people followin’ my guys - right behind ‘em! Oh, yeah, and terps, we have seven terps with us, and now YOU. Can you see why I wouldn’t fuckin’ want you on this mission?”

I remained silent. No answer I could produce would help me. Besides, it was rhetorical, I think.

“Who sent you here any fuckin’ way?”

“The colonel said I could choose who I wanted to cover based on what shots I needed and I want to be with the main effort,” I said.

He paused, turned, looked in my eyes, then pursed his lips.

“Well, if the Colonel wants you here and he said that, then I guess you’re coming with us aren’t you,” he shook his head but didn’t mean to and stopped himself. “But I don’t have to like it and if you can’t hang, we’ll cut ya loose. The first three days we walk in, conduct an op, then walk to the next one. We carry everything we’ll need.”

I stood straight, listened and remained silent, nothing to say really, other than ‘yes, sir’.

“We’re gonna look at what you’re takin’. If you’re coming with us, then you pack what’s on OUR packing list. If you got shit that’s not on there, then you’re not fuckin’ bringin’ it.”

“Sir, I already sent my ruck ahead with Bravo Company so…”

“Listen,” he interrupted. “I’m not gonna be fuckin’ haulin’ you all over the fuckin’ battlefield.”

“Yes, sir,” I said. I should have kept my mouth shut about my ruck.

He looked at my chest, nodding a bit, making it clear that he had seen my Expert Infantryman’s Badge, my Airborne wings, my Air Assault wings.

“I know you know what I’m talkin’bout. You have to prove yourself here. And if you do, you might be able to come out on other missions with us. – Hell, we might even request you by name.”

Half the guys in his unit had on their chests what I had on mine. It didn’t matter; what mattered was my performance. I had an ounce of credibility, but that wasn’t enough. I knew I needed to prove I could pull my own weight.

“Are there any fucking pens that work around here? … Ah, there we go,” slapping a pen and small tablet on the coffee table in the middle of the room, “Gimme your name and number. I’ll have my 1st Sgt. contact you with what you need to know.”

Alpha Company First Sergeant - May 23, 2004

I knocked on the same door, this time to see the 1st Sgt.

“Enter!” he replied.

I pushed the door open and stood in the same spot I had 24 hours before, the commander’s bunk on one side, the 1st Sgt.’s on the other. In the middle of the room, 1st Sgt. Jason Williams reclined in a chair, his feet on the coffee table where I’d written my name and number.

“Hi, 1st Sgt., I’m Sgt. Clawson with the Public Affairs Office here on camp,” I said.

He raised his eyebrows, his head canted down, his eyes looked up. He was telling me without saying it that he already knew all this… you are telling me things I already know, he looked intently at me – now stop and get on with it.

“I wanted to stop by and pin down the details for the air op,” I said.

“First off, what do you expect on this mission?” he was curt.

“I’m coming to get footage, still photos, and write stories 1st Sgt.,” I said, searching his face, trying to read him, gauging his response.

“No, you didn’t answer the fuckin’ question. What do you expect on this mission?” he asked again.

I really didn’t get the point he was driving, so I paused.

“Listen; if you think you’re going to go anywhere you want on the battlefield, you’re mistaken. You are the least of priorities,” he said, sizing me up.

“Roger, 1st Sgt.”

“Did you think I’d put you in the first chalk as one of the first off?” he questioned.

I didn’t respond.

“You’ll be with me, on serial three, chalk one. That’s the last of us. And no one will go up ‘til my guys have done their jobs and secured the area.”

“Roger, 1st Sgt.”

“I’ve got young guys on this mission. Young soldiers make mistakes, they screw-up sometimes,” he said.

I nodded, knowing exactly where he was headed.

“That’s the kinda story that if my soldiers read, they’ll lock up; if they read about how badly they handled the PUCs (persons under control, i.e. detained locals), they’ll be afraid to touch’em,” he said. “What I’m sayin’ is if all you show is what goes wrong, it’s over. I’ll sit you down and you’ll never come out with us again.”

Obviously he didn’t understand my job, as many soldiers don’t. I can only write good things about the Army, but I wasn’t about to educate him. I just acknowledged.

“Roger, 1st Sgt.”

“Don’t get me wrong, I want you on this mission. You are the one who ‘tells the soldier’s story’, but I have worked with public affairs before. Hell, I’ve worked with public affairs longer then you’ve been in the Army. Somma you guys are great, but somma you want to be Geraldo Rivera, get the story no matter what, and in the process endanger lives,” he said.

I had no response.

“Everyone wants a byline. I know how it works,” he said.

This time he expected a response.

“I want to do a good job 1st Sgt, but I’ll only go as far as you want me to,” I said.

“If you endanger the lives of my men, I will sit you down. And when we get back, I’ll tell your supervisor I never want to see you again,” he said.

I breathed in deep. I didn’t mean to, I just did. He noticed.

“But, like I said, I want you here, the guys like it when they see themselves on television or see some little bit in a paper,” he said.

I guessed this was the way the commander and first sergeant wanted to lay the framework in which I’d work. Playing bad cop, bad cop, had worked. I was tight as a drum. I’d better make sure nothing I did was out of line. This was to be my first operation and I knew I wanted more.

“If you don’t have fun out there, it’s your own fault,” he said, lightening me up as our chat ended.

“I mean, you do have a sense of humor, don’t you?” he quizzed me, a big grin on his face.

“Roger, 1st Sgt.,” I said, allowing my mouth to turn upward for the first time.

“’Cause if you don’t, you’re gonna be hurtin’,” he said. “Listen, be here at eleven forty-five zulu. We’ll be doing our PCI’s. You can get some shots of that.”

“Roger, 1st Sgt., thank you,” I turned and walked through the door.

Some stresses here come from just trying to get my foot in the door to get a story.

“Fuckin’ reporters!”

Bravo Company was to move into position two days prior by ground transport to provide support forming the objective’s outer cordon. Alpha Company was then to fly in on Blackhawk helicopters and assault the first objective from the outset. I wanted to fly with Alpha and the Battalion Commander had given me latitude to do so, yet I had to clear it with the Company leadership.

The following dialogue is what I poured onto the page right after I initiated contact with the Alpha Company leadership. It is rough, has rough language and, I think, gives a taste of the military environment.

This was to be the first time since Vietnam that Alpha 2-35 Infantry would engage an enemy in combat. The pressure was on the leaders. I had been in Afghanistan only a few weeks. This was to be my first air assault in combat as well.

I've altered names to protect identities.

Alpha Company Commander - May 22, 2004

Captain Eric Arnold seemed well educated. He’d been to college, probably an ROTC grad at 22. Yet, for years he’s been around infantrymen, his language natural, base, straightforward and genuine, an infantryman’s language. No holds barred. I stood erect in the entry way to his quarters and listened as he laid it on the line.

“To be honest with you, I don’t fuckin’ want you on this mission.” He kept talking to me while searching for something, rifling through stuff on a shelf, then on his bunk, then lifting papers at his desk.

“I’ve got too many strap-hangers as it is,” he said.

An Airborne term - ‘strap hangers’ – these were jumpers who weren’t part of the unit who show up at the last minute and want to be manifested for a jump. What could be a good jump with people you trust turns into an unpredictable gaggle of people you don’t know.

“It’s nothin’ ‘gainst you personally, you may be a great guy, but I don’t know you, my guys don’t know you. YOU are a liability to my unit,” continuing to search for something.

“Fuckin’ strap hangers… I’ve got interrogators, FBI, THT, female search teams, chaplains AND their assistants … fuckin’ chaplains! I gotta a whole gaggle of people followin’ my guys - right behind ‘em! Oh, yeah, and terps, we have seven terps with us, and now YOU. Can you see why I wouldn’t fuckin’ want you on this mission?”

I remained silent. No answer I could produce would help me. Besides, it was rhetorical, I think.

“Who sent you here any fuckin’ way?”

“The colonel said I could choose who I wanted to cover based on what shots I needed and I want to be with the main effort,” I said.

He paused, turned, looked in my eyes, then pursed his lips.

“Well, if the Colonel wants you here and he said that, then I guess you’re coming with us aren’t you,” he shook his head but didn’t mean to and stopped himself. “But I don’t have to like it and if you can’t hang, we’ll cut ya loose. The first three days we walk in, conduct an op, then walk to the next one. We carry everything we’ll need.”

I stood straight, listened and remained silent, nothing to say really, other than ‘yes, sir’.

“We’re gonna look at what you’re takin’. If you’re coming with us, then you pack what’s on OUR packing list. If you got shit that’s not on there, then you’re not fuckin’ bringin’ it.”

“Sir, I already sent my ruck ahead with Bravo Company so…”

“Listen,” he interrupted. “I’m not gonna be fuckin’ haulin’ you all over the fuckin’ battlefield.”

“Yes, sir,” I said. I should have kept my mouth shut about my ruck.

He looked at my chest, nodding a bit, making it clear that he had seen my Expert Infantryman’s Badge, my Airborne wings, my Air Assault wings.

“I know you know what I’m talkin’bout. You have to prove yourself here. And if you do, you might be able to come out on other missions with us. – Hell, we might even request you by name.”

Half the guys in his unit had on their chests what I had on mine. It didn’t matter; what mattered was my performance. I had an ounce of credibility, but that wasn’t enough. I knew I needed to prove I could pull my own weight.

“Are there any fucking pens that work around here? … Ah, there we go,” slapping a pen and small tablet on the coffee table in the middle of the room, “Gimme your name and number. I’ll have my 1st Sgt. contact you with what you need to know.”

Alpha Company First Sergeant - May 23, 2004

I knocked on the same door, this time to see the 1st Sgt.

“Enter!” he replied.

I pushed the door open and stood in the same spot I had 24 hours before, the commander’s bunk on one side, the 1st Sgt.’s on the other. In the middle of the room, 1st Sgt. Jason Williams reclined in a chair, his feet on the coffee table where I’d written my name and number.

“Hi, 1st Sgt., I’m Sgt. Clawson with the Public Affairs Office here on camp,” I said.

He raised his eyebrows, his head canted down, his eyes looked up. He was telling me without saying it that he already knew all this… you are telling me things I already know, he looked intently at me – now stop and get on with it.

“I wanted to stop by and pin down the details for the air op,” I said.

“First off, what do you expect on this mission?” he was curt.

“I’m coming to get footage, still photos, and write stories 1st Sgt.,” I said, searching his face, trying to read him, gauging his response.

“No, you didn’t answer the fuckin’ question. What do you expect on this mission?” he asked again.

I really didn’t get the point he was driving, so I paused.

“Listen; if you think you’re going to go anywhere you want on the battlefield, you’re mistaken. You are the least of priorities,” he said, sizing me up.

“Roger, 1st Sgt.”

“Did you think I’d put you in the first chalk as one of the first off?” he questioned.

I didn’t respond.

“You’ll be with me, on serial three, chalk one. That’s the last of us. And no one will go up ‘til my guys have done their jobs and secured the area.”

“Roger, 1st Sgt.”

“I’ve got young guys on this mission. Young soldiers make mistakes, they screw-up sometimes,” he said.

I nodded, knowing exactly where he was headed.

“That’s the kinda story that if my soldiers read, they’ll lock up; if they read about how badly they handled the PUCs (persons under control, i.e. detained locals), they’ll be afraid to touch’em,” he said. “What I’m sayin’ is if all you show is what goes wrong, it’s over. I’ll sit you down and you’ll never come out with us again.”

Obviously he didn’t understand my job, as many soldiers don’t. I can only write good things about the Army, but I wasn’t about to educate him. I just acknowledged.

“Roger, 1st Sgt.”

“Don’t get me wrong, I want you on this mission. You are the one who ‘tells the soldier’s story’, but I have worked with public affairs before. Hell, I’ve worked with public affairs longer then you’ve been in the Army. Somma you guys are great, but somma you want to be Geraldo Rivera, get the story no matter what, and in the process endanger lives,” he said.

I had no response.

“Everyone wants a byline. I know how it works,” he said.

This time he expected a response.

“I want to do a good job 1st Sgt, but I’ll only go as far as you want me to,” I said.

“If you endanger the lives of my men, I will sit you down. And when we get back, I’ll tell your supervisor I never want to see you again,” he said.

I breathed in deep. I didn’t mean to, I just did. He noticed.

“But, like I said, I want you here, the guys like it when they see themselves on television or see some little bit in a paper,” he said.

I guessed this was the way the commander and first sergeant wanted to lay the framework in which I’d work. Playing bad cop, bad cop, had worked. I was tight as a drum. I’d better make sure nothing I did was out of line. This was to be my first operation and I knew I wanted more.

“If you don’t have fun out there, it’s your own fault,” he said, lightening me up as our chat ended.

“I mean, you do have a sense of humor, don’t you?” he quizzed me, a big grin on his face.

“Roger, 1st Sgt.,” I said, allowing my mouth to turn upward for the first time.

“’Cause if you don’t, you’re gonna be hurtin’,” he said. “Listen, be here at eleven forty-five zulu. We’ll be doing our PCI’s. You can get some shots of that.”

“Roger, 1st Sgt., thank you,” I turned and walked through the door.

Some stresses here come from just trying to get my foot in the door to get a story.

“Fuckin’ reporters!”

US Medic Helps Afghan Boy

For local Afghans in a rural province north of Kandahar, the small 50 troops based in an orchard during a week of pre-election operations meant it was an opportunity for much needed medical treatment.

This 8 year old boy had been dragged by a spooked mule while his foot was caught in the stirrup. The kid was kicked several times by the animal. A local "doctor" had put 70+ stitches in his head with regular thread three weeks prior to these photos.

The medic spent an hour removing the thread.

A place for my photos and stories

Over the course of my travels in Afghanistan I took hundreds of photos, shot a few videos and wrote about my experiences. I am only now beginning to share these pieces online. I hope you enjoy the content and let me know your thoughts on each piece. I am very selective about the few photos I post -- only my best will find their way into the blog.

Again, enjoy.

Cheers,

Jeremy Andrew

Again, enjoy.

Cheers,

Jeremy Andrew

Afghan Girl Fall 2004

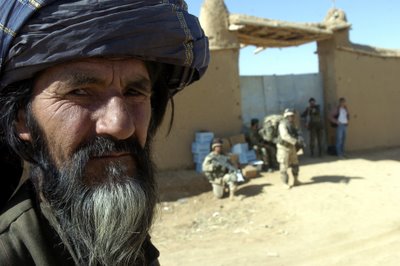

The village center was filled with men and a few boys we learned as we gathered the people to be questioned and searched in the pursuit of Taliban and insurgents.

The village center was filled with men and a few boys we learned as we gathered the people to be questioned and searched in the pursuit of Taliban and insurgents.The only female in the open was a toddler lying in a shop doorway. She was adorned in velvet and beads, bracelets and a head scarf. She did not move as her father and brother were shuffled to the end of the street with the other males.

Motionless, seemingly already beaten by life, she only moved her eyes as US soldiers moved about the market.